This EDP Wire was originally published with the German Development Institute (DIE) as Briefing Paper 21/2021.

Summary

The question of whether and how democracy can be promoted and protected through international support has recently gained relevance. On the one hand, the withdrawal of NATO troops from Afghanistan has reignited a public debate on the limits of democracy promotion. On the other hand, the need for international democracy protection is growing due to an increase in autocratisation trends worldwide. DIE research shows that it is possible to effectively support and protect democracy. In this context, both the protection of central democratic institutions, such as term limits for rulers, and the promotion of democratic forces that pro-actively resist attempts at autocratisation are central. Since 2010, autocratisation trends have been characterised by the fact that they often slowly erode achieved democratisation successes and consolidate autocracies. The circumvention and abolition of presidential term limits by incumbent presidents are part of the typical “autocratisation toolbox”. Term extensions limit democratic control and expand presidential powers. Democracy promotion and protection play a relevant role in preserving presidential term limits, and thus in protecting democracy. They contribute towards improving the “duration” and “survival chances” of presidential term limits. The more international democracy promotion is provided, the lower the risk that term limits will be circumvented. For example, a DIE analysis found that a moderately high democracy promotion mean of $2.50 per capita over four years on average halves the risk of presidential term limits being circumvented.

Based on quantitative analysis and case studies, the following recommendations for international democracy promoters emerge:

• Use democracy promotion and protection in a complementary way. On the one hand, democracy must be promoted continuously, as the organisational and oppositional capacity of political and civil society actors can only be built up in the long term. On the other hand, democracy protectors must also react in the short term to political crises with ad hoc measures and diplomatic means.

• Democracy promotion is a risky investment that pays off. Whether it is possible to promote democracy in the long term and protect it from autocratisation depends above all on domestic forces and institutions. For them, too, political crises are openended. While inaction tends to play into the hands of autocrats, context-sensitive engagement at least offers the possibility of contributing to the preservation of democracy.

• Strengthen democracy protection through regional organisations. Regional organisations such as ECOWAS and the African Union offer regional political structures that can help with de-escalation and ensure credible commitments on the part of the incumbents. International donors could therefore coordinate with regional organisations in situations where democracy is at stake.

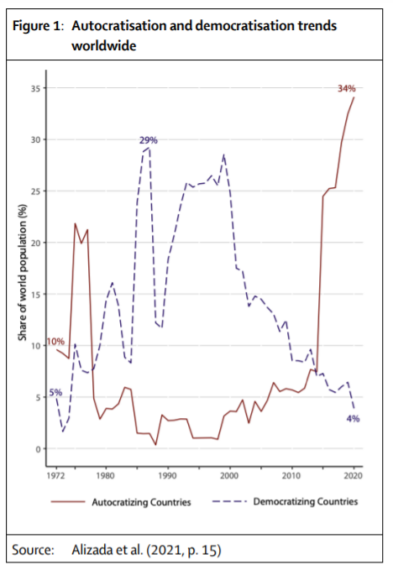

If one observes political trends since the turn of the millennium, there is good news and bad news. The bad news first: The democracy euphoria that began with the fall of the Berlin Wall in the 1990s has come to an end. Instead of expanding and improving qualitatively, many democracies around the world are experiencing antipluralisation and autocratisation trends (Figure 1). Some autocracies are also becoming more autocratic. In 2020, autocrats ruled 68 per cent of the world’s population (Alizada et al., p. 8). These trends do not stop at established democracies such as the United States, India and Brazil; they are spreading within the European Union (especially Hungary and Poland) and also leading to the dismantling of democracies and the expansion of autocracies (e.g. Turkey, Cambodia). As a result, more and more people are experiencing political insecurity and human rights violations in addition to no longer being able to express their opinions or participate freely in public life. The good news is that democratic forces from the political opposition, civil society and business are resisting autocratisation tendencies. In the very early stages, established institutions such as courts and parliaments can act as bulwarks against attempts at autocratisation. Even in autocracies, democratic forces do not tire of campaigning for more freedom and political equality (e.g. Sudan, Thailand, Turkey). At the same time, the downward trend in democratisation (Figure 1) should not obscure the fact that the global cross-section of current regime changes also conceals democratisation successes, such as in Armenia, Ecuador and South Korea.

The current wave of autocratisation came gradually. In many countries, it often did not manifest itself – as it did in the 1980s – with a sudden collapse of the regime, for example through a military coup. Rather, in many places elected governments have dismantled democratic institutions and rules from within. The typical “toolbox” of autocrats or those who want to become one includes, above all, limiting democratic control and expanding their own powers. Reforming constitutions, manipulating the political opposition, preventing civil society forces from acting through legal restrictions, limiting the powers of the courts and silencing the critical public are just a few examples. The removal of presidential term limits is also a popular tool.

Does democracy promotion help preserve presidential term limits?

Protecting and promoting democracy through international cooperation becomes more important in this global context. Through financial and political support and empowerment, international actors can support democratic forces and institutions towards working effectively for the protection of domestic democracy, despite the lack of a “level playing field”. As findings from DIE’s research show, this also applies to the preservation and protection of term limits (Leininger & Nowack, in press; Nowack & Leininger, in press). The analysis included data on 93 tenure restrictions from 63 African and Latin American countries and examined circumventions of tenure restrictions between 1990 and 2014.

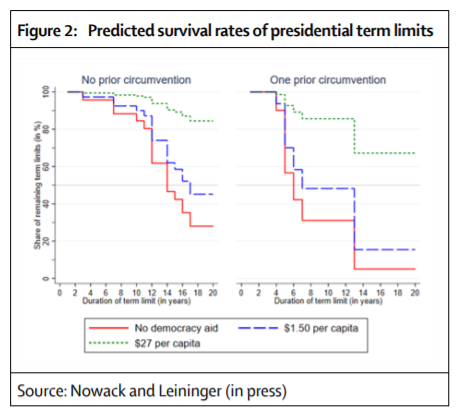

The results of the study show with high statistical probability that the higher the level of international democracy support, the lower the risk of circumventing presidential term limits. For example, the analysis shows that a moderately high level of democracy support averaging $2.50 over four years reduces the risk of circumventing presidential term limits by an average of 46 per cent.

Based on the study results, the effect of democracy support on the “survival rates” of term limits can be estimated (Figure 2). The estimation applies to country profiles that are typical for circumventing term limits: countries in which institutions of liberal democracy are not consolidated, receive comparatively low levels of official development assistance and are neither politically allied nor at odds with their donor countries. Low levels of democracy support have only a weak positive effect on the survival rate of tenure restrictions in such contexts (blue dashed line in Figure 2). Moderate to high levels of democracy promotion (the area between the blue and green lines in Figure 2), on the other hand, increase the duration that term limits remain in place, and they substantially increase the proportion of term limits that remain in place beyond 20 years. In contexts where a previous term limit has already been circumvented once, this difference is particularly pronounced. Whereas with no or only low levels of democracy support, the “survival probability” of a further term limit is estimated at less than 20 per cent; with high levels of democracy support, it is estimated at almost 75 per cent.

Which democracy promotion measures are effective?

In order to shed more light on the mechanisms through which international democracy promotion contributes to the preservation of presidential terms in office, it is worth analysing specific country contexts. In Malawi, an attempt by the incumbent to have the term limit lifted by parliament failed in 2002/2003. In Senegal, the incumbent, Abdoulaye Wade, managed to run again in 2011/2012 through a court order, but he lost the subsequent presidential election.

In both cases, international democracy promotion was crucial for the extra-parliamentary, civil society opposition. As incumbents, the presidents were able to act from a strong position, and thus to partly use state resources to force political manoeuvres and suppress the opposition. They made use of a wide range of instruments, from influencing court rulings (e.g. electoral admission), issuing bans on demonstrations and bribing members of parliament to the violent intimidation of parliamentary and extra-parliamentary opposition. In both cases, the long-term support of civil society organisations and social movements by international democracy promoters was a key resource for the organisation of political opposition.

Another shared feature of the cases is the course of action that international democracy supporters steered towards the incumbents. In both the Malawian and Senegalese cases, international donors publicly condemned the actions of the incumbents. By speaking out publicly in favour of freedom of assembly and demonstration, they helped to legitimise extra parliamentary opposition. They complemented this strategy with informal, bilateral talks that exerted (economic-political) pressure on the respective incumbents.

However, both cases also show path- and contextdependent differences. Because in the Senegalese case the incumbent was already able to secure admission to candidacy by court order, the presidential elections represented the decisive political arena. Focusing on these issues – as well as on supporting an anti-term extension campaign during the run-up to the election – was therefore crucial. Furthermore, international election observation by ECOWAS led to a high level of legitimacy of the presidential elections, forcing the incumbent to accept his defeat. In Malawi, on the other hand, the incumbent attempted to circumvent term limits through parliament, rendering it the decisive political arena. The decisive factor for the outcome of the circumvention attempt was therefore that international pressure from donors – in combination with extra-parliamentary, civil society opposition – gradually eroded the incumbent’s parliamentary support within and beyond his own party.

Conclusions and implications

Democracy promotion can be a relevant factor for the preservation of presidential term limits and thus protect democracy. However, democracy supporters have to keep in mind that anything that is worth doing, is worth doing well, and this counts especially for protecting and promoting democracy.

• Use democracy promotion and protection in a complementary way. On the one hand, democracy must be continually promoted and supported, as the organisational and oppositional capacity of political and civil society actors can only be built up in the long term. This also includes the continuous protection of the civic space. For this, both non-governmental organisations and informal civil society actors (e.g. social movements) must be supported. On the other hand, donors who aim to protect and promote democracy must also be prepared to react with ad hoc measures (e.g. conditionality) and diplomatic means if the political situation in the country comes to a head.

• Democracy promotion is a risky investment that pays off. Whether it is possible to promote democratic institutions and attitudes in the long term and protect democracy from autocratic tendencies depends above all on domestic forces and institutions. Political crisis situations are characterised by a high degree of insecurity, and democratisation processes are openended, so success is not guaranteed. Whereas doing nothing leaves democratic domestic forces in the lurch and tends to play into the hands of autocrats, contextsensitive engagement still offers the possibility of making a contribution.

• Strengthen democracy protection through regional organisations. Regional organisations such as ECOWAS and the African Union offer regional political structures that can help with de escalation and ensure credible commitments on the part of the incumbents. International donors could therefore coordinate effectively with regional organisations in situations where democracy is at stake.