This EDP Wire was originally posted on blogs.lse.ac.uk. The article argues that the EU enlargement process in the Western Balkans has fallen short of reproducing the transformative impact it had in Central and Eastern Europe. EDP member Solveig Richter and Natasha Wunsch point to state capture as the core obstacle to deep democratisation in the region and argue that EU conditionality not only fails to overcome detrimental governance patterns, but unintentionally contributes to entrenching them. Only by extending its engagement beyond the dominant executive and favouring domestic deliberation over incentive-driven compliance can the EU expect to change the situation for the better.

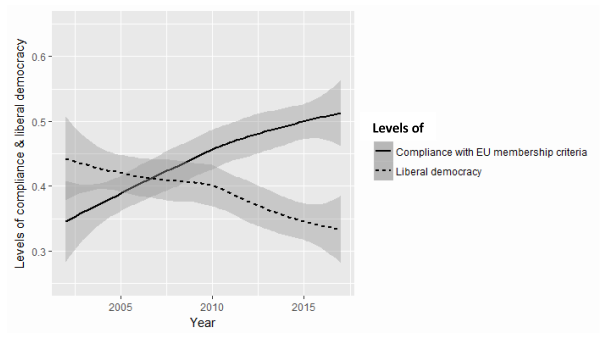

Political conditionality is the major instrument through which the European Union has sought to foster democratic reforms in the Western Balkans. Yet, it is increasingly obvious that this classic tool of enlargement policy is failing to create the conditions required in a fragile post-conflict context to successfully tackle simultaneous political and economic reform. Instead, there is a striking decoupling between a steady increase in levels of formal compliance with EU accession conditions, and the simultaneous decline of liberal democracy across the region, with country-level trends ranging from stagnation to outright regression.

Figure 1: Decoupling of compliance and democracy levels in the Western Balkans

In a recent study, we found evidence to suggest that the observed decoupling is due to widespread state capture that prevents governments in the region from pursuing effective democratic transformation. State capture describes a particularly destructive form of corruption whereby state institutions and intermediary actors, such as political parties, become hijacked or infiltrated by clientelist networks that use them to lend their informal practices a formal mantle.

In its 2018 strategy for the Western Balkans, the European Commission identified state capture as a major impediment to deep reforms in the Western Balkans, claiming that ‘(…) the countries show clear elements of state capture, including links with organised crime and corruption at all levels of government and administration, as well as a strong entanglement of public and private interests.’ Yet, EU conditionality has not only failed to effectively address state capture, but also unintentionally contributes to consolidating such processes by enabling informal networks to strengthen their grip on power.

Detrimental effects of EU conditionality

Why has the EU’s conditionality approach succeeded in fostering compliance with the EU’s formal accession criteria, but fallen short of setting the Western Balkan countries onto a sustainable path towards democratisation? To understand this paradox, we must systematically factor informal domestic politics into the analysis and examine the (unintended) negative effects of the EU’s enlargement policy. We do not claim that the EU caused state capture in the first place, as this is a multi-causal process that tends to emerge across a range of transition contexts. Still, it has contributed to entrenching such detrimental governance patterns in several ways.

We identify three distinct linkages that connect EU conditionality to the consolidation of state capture. First, external pressure for the liberalisation of markets in the absence of a comprehensive legal framework allowed a small economic elite to realise private gains and build powerful networks that influence political decision-making (money). Second, strong top-down conditionality stifles domestic deliberation and weakens internal mechanisms of accountability, allowing ruling elites to silence domestic opponents (power). Finally, progress towards EU membership and frequent interactions with high-ranking EU and member state officials serve to legitimise ruling elites (glory). As a result, the countries of the Western Balkans are stuck in a ‘state capture trap’ that leads to stagnating democratisation and the inability to implement deep reforms.

Figure 2: EU conditionality and the state capture model

The way forward: Beyond executive engagement

So must we conclude that the Western Balkans countries are a lost cause for democracy and the rule of law? To the contrary. Tens of thousands of protesters across the region are demanding political change, including large-scale demonstrations against the Serbian president in Belgrade and the north of Kosovo. The EU remains the most important external driver for such change. Still, the current conditionality approach risks strengthening state capture even further. Nor will the mere refinement of conditionality be sufficient to tackle the widespread disablement of domestic checks and balances across the region.

If thorough democratic transformation still remains the EU’s goal in the region, conditionality needs to be complemented with a more comprehensive and deliberate empowerment of national parliaments and civil society actors as a counterweight to dominant executives. Favouring domestic deliberation rather than incentive-driven compliance should go a long way in ensuring the sustainability of rule of law and democratic reforms even once the Western Balkan countries have eventually become EU members.

For more information, click here to see the authors’ accompanying article in the Journal of European Public Policy.